Database internals: page buffer pools

---------------------------------------------------

Latency Numbers Every Programmer Should Know

---------------------------------------------------

L1 cache reference 0.5 ns

Branch mispredict 5 ns

L2 cache reference 7 ns

Mutex lock/unlock 25 ns

Main memory reference 100 ns

Compress 1K bytes with Zippy 3,000 ns

Send 1K bytes over 1 Gbps network 10,000 ns

Read 4K randomly from SSD* 150,000 ns

Read 1 MB sequentially from memory 250,000 ns

Round trip within same datacenter 500,000 ns

Read 1 MB sequentially from SSD* 1,000,000 ns

Disk seek 10,000,000 ns

Read 1 MB sequentially from disk 20,000,000 ns

Send packet CA->Netherlands->CA 150,000,000 ns

Source: Colin Scott

https://colin-scott.github.io/personal_website/research/interactive_latency.html

Reading from disk is really, really slow. So, how do databases store large amounts of data without sacrificing performance? The answer is by using page buffer pools.

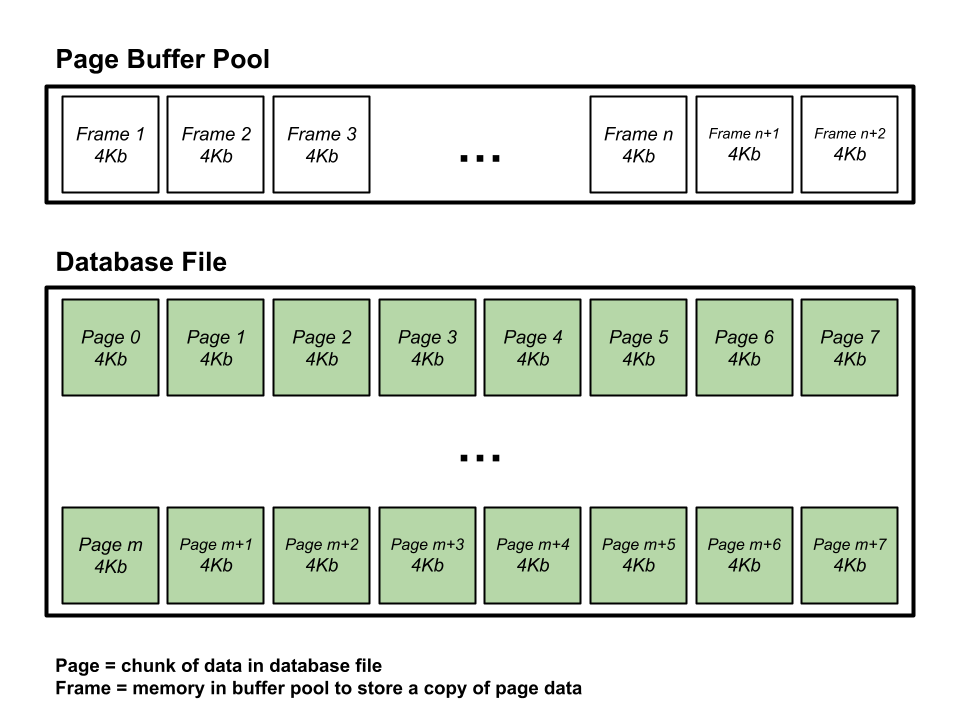

When a database stores information on disk, data is typically stored in chunks called pages. In most database implementations, page sizes range from 2 KB to 64 KB (with some as large as 256 KB!), with most databases using 4 KB, 8 KB, or 16 KB pages.

While the database is running, a large memory allocation is made to create a buffer to store these pages—this is known as the page buffer. The buffer contains many slots called frames, each used to store a copy of a page.

After the initial performance cost of copying the entire page into memory, all subsequent reads from the page are significantly faster than accessing it directly from disk due to the difference is access times of memory vs disk.

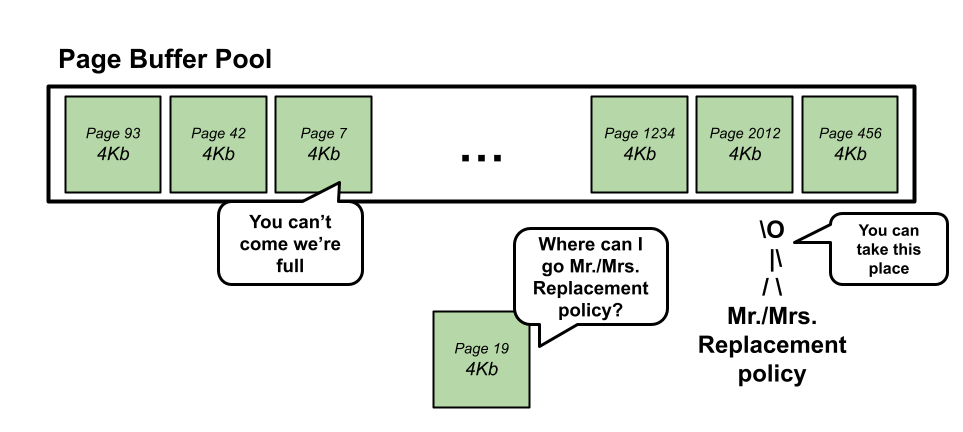

Sounds simple enough. But there’s an important question left to answer: what

happens when the buffer fills up? As mentioned earlier, we can’t fit all

the data into memory (what if the database contains multiple gigabytes of data?).

In such cases, some of the pages in the buffer need to be removed. But which ones?

And how?

Databases use replacement policies, which dictate which pages in the buffer

should be removed and replaced by new ones. Many such policies exist, including

LRU (Least Recently Used), clock, random replacement (RR),

and others.

Each replacement policy has its pros and cons and is suited to certain access

patterns better than others.

Once a replacement policy is selected, the buffer pool can evict pages accordingly.

Importantly, because most databases support both reading and writing, the buffer

pool must also track whether a page has been modified—whether it’s dirty.

This is typically done using a bitfield called a dirty bit. If the dirty bit

is set (meaning the page has been modified), the database must write the updated

page back to its location in the database file before eviction. If the bit is

not set (i.e., the page hasn’t been modified), the page can be replaced

immediately by another page.

/*

A page buffer pool might contain a map from page IDs to some type of page

metadata, which includes information such as:

- The frame containing the page

- Whether the page has been modified (is it dirty?)

- Other possible fields, such as reference counts to the page, etc.

*/

struct PageMeta {

frame_id_t frame_id;

bool is_dirty;

...

};

When implemented correctly, the page buffer pool should be completely invisible to the user, automatically copying and evicting pages as needed to perform efficient reads and writes.

Note: A subsequent post may be made in the future to discuss some of the performance trade-offs between different replacement policies.